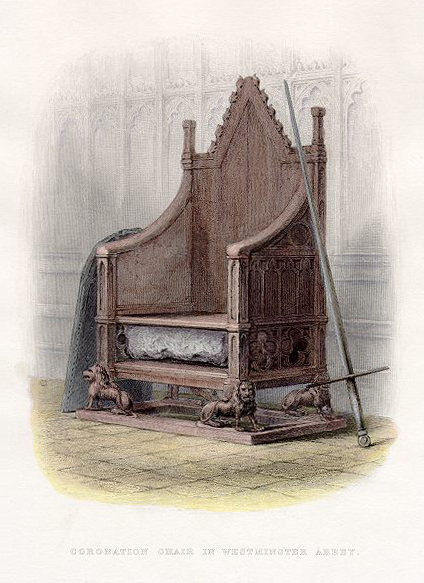

Some of you may have noticed a large stone, hiding underneath the seat of King Edward’s coronation chair, as it’s called. But what is the stone? And why is it there?

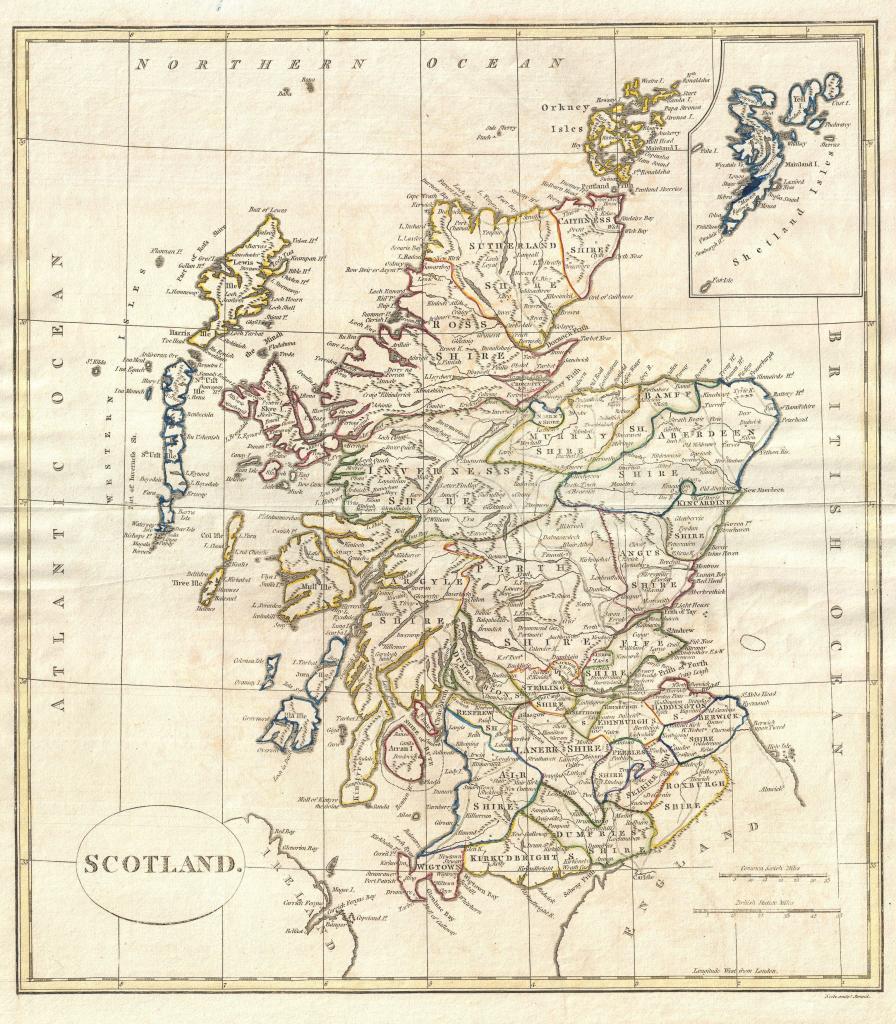

First off, it’s called ‘The Stone of Scone’. No, it’s not the delicious sort with jam and cream, this stone is from Scone Abbey, in Perthshire, Scotland. The history of the stone is wrapped in mystery and myth, with some claiming it dated from biblical times as the Stone of Jacob. Others claimed Fergus, son of Eirc, the possible first King of the Scots, brought with him from Ireland, where it had been used for crowning the Irish High Kings. However, historians have since tested the stone, identifying it as red sandstone found in the vicinity of Scone, so actually it hadn’t travelled far! It was used from Scone’s Abbey’s inception as a part of the ceremony for crowning a Scottish monarch. At the coronation of a new Scottish king, they would sit upon the stone (also known dramatically as ‘The Stone of Destiny’) to be inaugurated.

So what is a Scottish stone for Scottish coronations doing in a chair in Westminster? For that, we have to go back to the 13th century, and the reigns of Edward I of England, and Alexander III of Scotland. In the 1280s, Scotland and England got on quite well together. Alexander III paid homage to his cousin, Edward I, for some lands he held in England, and there was no conflict between the two kingdoms. But then in 1286, Alexander died. This wouldn’t normally have been so terrible, except…he only had one heir. He had three children that survived infancy, but one of his sons, David, died at the age of 9, his other son, Alexander, died at 20 years old, and that left only his daughter, Margaret.

At the age of 20, she was married to King Eric II of Norway (who was himself just a young teenager), and they in turn had a daughter, known as Margaret, the Maid of Norway. Sadly, the elder Margaret died in childbirth, leaving little Margaret as Alexander III’s only heir. In 1286, she was just three years old, but she was now required to be queen of Scotland. Understandably, her father was reluctant for his toddler daughter to be sent away to a different country, especially as she wasn’t going to be able to rule alone until the age of majority. Eric also didn’t really know what the state of the kingdom was like, as Robert de Brus, 5th Lord of Annandale (grandfather of the famous Robert the Bruce) was kicking off a rebellion over who should actually claim the throne of Scotland.

But then came an unexpected twist – Edward I got involved. Eric turned to the older king for advice, and ended up negotiating a marriage with him. It was agreed that little Margaret would, when old enough, marry Edward of Carnarvon, Edward I’s son. So finally, a few years later in 1290, Eric agreed to send his daughter to Scotland, but only via England so she could start her journey under Edward I’s protection. Margaret was just six years old. Unfortunately, she fell ill on the ship crossing from Norway with what was likely food poisoning – much more deadly in those days than it is now – and died in September of that year in Orkney, in the arms of Bishop Narve, who had been part of her entourage.

Aside from the tragic death of such a young life, Scotland was now in a succession crisis. Around 14 claimants put their claims to the throne forward, but there were only two claimants with any real contest; John Balliol and Robert de Brus, 5th Lord of Annandale. Edward I was invited to come and keep an eye on the proceedings and administer the events, but not to actually take any part in the decision. Now, while little Margaret had lived, Edward hadn’t been too bothered about running things in Scotland, since she was going to marry his son, and their children in turn would inherit both of the kingdoms of England and Scotland. Unfortunately for the Scottish nobles, her death now meant Edward was interested. When he arrived, Edward announced if we was going to oversee proceedings, he would be in charge instead, as Scotland’s feudal overlord.

Obviously, none of the nobles were happy about this, but as none of them were higher in rank than he was, they reluctantly agreed Edward could remain in this position until a successor was chosen. After long discussions and much soul-searching, the magnates finally chose John Balliol as their new king on the 17th November 1292. But the issue was…Edward just wouldn’t hand over to the new monarch. He continued to involved himself where he wasn’t wanted. Edward agreed to hear appeals to cases that had been decided by the governors of Scotland while they were choosing a new king, as well as demanding the new Scottish King John appear before the English Parliament to answer to a case – which, for King John’s part, he actually did. But then Edward demanded Scottish soldiers to fight for him against France, and that pretty much decimated any good feeling left between the English king and the Scottish court. Just to make sure he got the message, Scotland, instead of sending him soldiers, made an alliance with France – the origins of the ‘Auld Alliance’.

This launched the First War of Scottish Independence, and a series of tit-for-tat battles began. Scotland attacked Carlisle, and Edward took Berwick-Upon-Tweed to retaliate. In 1296, Edward’s forces won over the Scottish resistance at the Battle of Dunbar, and as punishment (for something he had started with his actions in the first place) Edward took the Stone of Scone, and transported it back to London with him. The message was clear; he was in charge of Scotland, therefore he was effectively Scotland’s ruler. Just to really hammer home the point, Edward also deposed John Balliol and threw him into the Tower of London, putting English nobles in charge of running Scotland – which wouldn’t end well, by the way.

In the meantime, Edward drew up plans for a fancy new chair for his stolen stone, commissioning Walter of Durham in March 1300 to make it. It was to be carved from oak, but also decorated with coloured glass and gilding, much of which has sadly been lost. Interestingly, it’s actually the oldest piece of English furniture made by someone we know the name of. It wasn’t intended to be used as a coronation chair, but at some point in the 14th century, that’s exactly what it began to be used as. Monarchs sat directly on the stone until the 17th century, when a wooden seat was added above it.

There were attempts to get the stone back to its rightful country! In 1328, an agreement was made to bring the First Scottish War of Independence to an end. England agreed to give the stone back, but crowds rioted outside Westminster and prevented it being brought out. Many centuries later, in 1950 on Christmas Day, four Scottish students from the University of Glasgow (Ian Hamilton, Gavin Vernon, Kay Matheson, and Alan Stuart, respectively) commandeered the stone from the Abbey and set off with it. During the heist, the stone broke into two pieces, but they managed to get the two parts up into Scotland separately. Once back in Scotland, the Stone of Scone was passed to a Glaswegian politician, who arranged for a stone mason to fix it.

The British government issued a nationwide search for the stone, and eventually it was left, on the 11th April 1951, on the steps of Arbroath Abbey, a property belonging to the Church of Scotland. This was England’s chance to hand it back, but instead, it was recovered and brought back to Westminster. Two years later, it would be used for Elizabeth II’s coronation. Rumour has it, however, that the stone left at Arbroath was in fact a fake, and the real Stone of Scone had quietly been smuggled back into Scotland.

Whatever the truth, you might be pleased to hear that eventually (some might say much later than it should have been!), the British government realised they still stolen Scottish property hanging out in Westminster Abbey, and it was given back to Scotland. It’s now part of the Scottish Crown Jewels in Edinburgh, and only comes back down to Westminster Abbey for the coronation of a new British monarch.

So there you have it! The reason every British monarch now sits on a lump of stone in an old wooden chair. If you want to know more about King Edward’s Chair, as well as other aspects of the British coronation, check out my new video ‘Origins of the British Coronation’ below. Thanks for reading, and come back for more forgotten history posts soon!